27 February 2015“… the experience of being at home can only be produced by rendering some others homeless.” The postcolonial observation of Aamir R. Mufti appears as a tragic template for our questions of land, always there behind the current discussions on land acquisition and its legality. Are the polar confrontations of increasingly radical policies with confounded resistances pointing towards the last decades of our deepest, oldest and most fundamental assumptions about land? Recent turns in the shared lexicon of educated and ruling classes seem to indicate this transition: Politics, limited by the walls of our polis, of our cities, our fields and our nations, is reaching its limits and metamorphoses to become Governance, the refinement of the Greek idea of the kubernan, of the principle of guidance, of projection onto a collective future. Yes, ancient societies knew of the possibilities of total alternatives, but many of these potentials remained on the far margins, while our politics took superficial adjustments for revolutions. In our Inter-actions dialogue on the roots and branches of the new Bill on land acquisition, Divya Trivedi measures the extent of detachment from the people’s concerns that ruling powers have developed. She recognises politics as usual in their tragic conformism to existing paradigms of political economy. Dunu Roy draws the backdrop of the birth of the Land Acquisition Act in India, and follows its growth over a century, finding an unfortunate coherence between a divinely ordained Crown and the surrender of party politics to neo-liberal programmes. He calls for the reclamation of the State and its instrumentality, an ambitious work of imagination and pragmatics, as shows C.R. Yadu in his spatially-specific reflection. In spite of socialist efforts with land, the latter remarks, Kerala demonstrates the difficulties, but also the urgent need, of translating the words of our principles and our laws, into transformative realities on the ground. Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations. |

|||||||||

Preparing a Future of ConflictsDivya Trivedi |

State of ReclamationsDunu Roy |

||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Even as billions of dollars of investments were being pledged at the 7th Vibrant Gujarat Summit in January this year, there was a crackdown on the various farmers’ organisations outside Gandhinagar that were planning a demonstration for the revision of the Minimum Support Price for cotton. This happened against the backdrop of reports of farmer suicides in the villages Dharai, near Chotila, and Fatehpur, near Patdi among other places in the Saurashtra region. In a bid to lay out the red carpet for big businesses in India, the Government is being apathetic to the concerns of its own citizens, treating them as roadblocks or hindrances on the path to ‘development’. Forced evictions and a disregard for basic human rights in pushing the land acquisition agenda of the dispensation have become the norm. Through the proposed Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Amendment) Bill, 2015, introduced in the Lok Sabha on 24 February, we observe an attempt to dilute the 2013 Act and do away with important safeguards for farmers and land owners. Chief among them is the Social Impact Assessment (SIA), to determine who the affected people are and to ensure the prior consent of affected people for private or Public Private Partnership projects (PPP). The process of seeking the consent of 70 per cent of affected people for PPP projects and 80 per cent for private sector projects will cease to exist if the amendments go through.

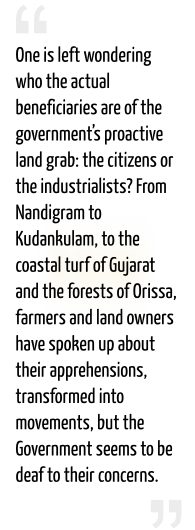

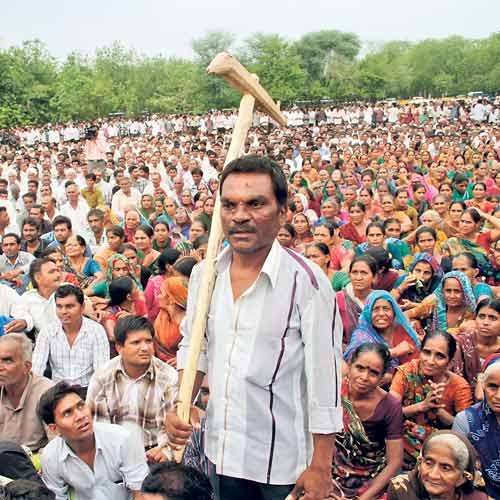

The Government has a right to acquire land for public purposes, for building roads, infrastructure, irrigation, etc., but it is increasingly doing it forcibly and at the cost of the rights of its citizens, for whom it claims to be building the projects. One is left wondering who the actual beneficiaries are of the government’s proactive land grab: the citizens or the industrialists? From Nandigram to Kudankulam, to the coastal turf of Gujarat and the forests of Orissa, farmers and land owners have spoken up about their apprehensions, transformed into movements, but the Government seems to be deaf to their concerns. Kundankulam’s nuclear power plant:

example of a ‘necessary’ land acquisition The amendments are also hastily overturning farmer-friendly ordinances in the LARR Act 2013. When farmers and activists went to submit a memorandum to the Collector in Bhavnagar, he refused to accept the memorandum, citing the prevalence of swine flu in Gujarat! “No police permission for rallies, marches, demonstrations, sit-ins. And now swine flu even for a memorandum!! Where should the farmers go for justice? When the farmers persisted with their demand for acceptance of the memorandum, the police was called in and around 50 people were arrested. This is the state of our democracy,” said a joint statement by the Gujarat Khedut Samaj and Jameen Adhikar Andolan Gujarat. Another ‘Vibrant Gujarat’:

large farmers’ protests in the supposed land of ‘development’ There is a sustained farmers’ movement in Gujarat for some time now, but it does not make it to the front pages of mainstream media. Vibrant Gujarat does. A circular issued by the Ministry of Environment & Forests in 2009 empowered the Gram Sabhas or village assemblies to a certain extent. It required the State Government to get a written consent or rejection of the Gram Sabha for the diversion of any forest land for non-forest use. But that is being actively subverted through various means. Earlier this month, a circular issued by the MoEF exempted linear projects such as roads, canals, laying of pipelines, optical fibre lines and transmission lines from seeking Gram Sabha consent. According to activist Kanchi Kohli, these cannot be viewed in isolation and are often integral components of power plants, mines and industrial estates. “Removing them from the overall context of land use change can lead to a fait accompli situation. The project proponent, having invested in a road and railway line, is likely to negotiate with an upper hand, citing that it has already ‘invested’ in the project and thereby demanding speedy approval for other components.”

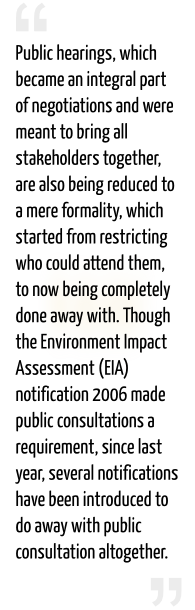

Public hearings, which became an integral part of negotiations and were meant to bring all stakeholders together, are also being reduced to a mere formality, which started from restricting who could attend them, to now being completely done away with. Though the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) notification 2006 made public consultations a requirement, since last year, several notifications have been introduced to do away with public consultation altogether. Projects above a certain capacity for coal mining and irrigation and “all linear projects such as highways, pipelines, etc. in border states” are some of the projects being exempted. Other controversial portions of the Bill state that poor farmers who cultivate lands but are not the owners will not be compensated and fertile land will also be acquired. As per the existing law, land will be given back to the farmer if it remains unused for five years but the proposed amendment states that the land will be returned only if the project fails to complete the deadline. Land acquisition used to be a colonial brutal exercise where the acquirer-Government could take any land it wished as per the Land Acquisition Act 1894. The 2013 Act brought in by the United Progressive Alliance II government sought to undo some of these feudal practices and bring in some sense of professionalism to the land grab process. It is another matter that some of the progressive laws that were brought in to safeguard the rights of land owners, while good on paper, had miles to go before they could be called successful in practice. But what the Bharatiya Janata Party Government is doing is clearly not in the best interests of the people and majorly tilted towards being pro-capital. Jantar Mantar welcomed peasant communities

to support a wide opposition to the Bill There has been opposition from several quarters regarding this Bill. Anti-corruption crusader Anna Hazare held protests and the Congress conducted a mega rally at Jantar Mantar, Delhi against the Bill. Most of the opposition parties, including Trinamool Congress, JD(U), Aam Admi Party, Left parties and others, vehemently opposed it. It is another matter that when the BJP was in the Opposition, Rajnath Singh was opposing certain clauses of this Bill himself. But that, as they say, is another story. Nevertheless, it will not be easy for the Government to push through the Bill. In any case, if it fails to pass it in this session, it will lapse and cannot be introduced again. In its fulfilment of capitalistic urges, the State is doing irretrievable harm to the balance between ecology and communities that have existed in harmony for years. Destroying forests and villages mindlessly to build factories and mines can only create a dystopian future, consumed by constant social and political conflict.

|

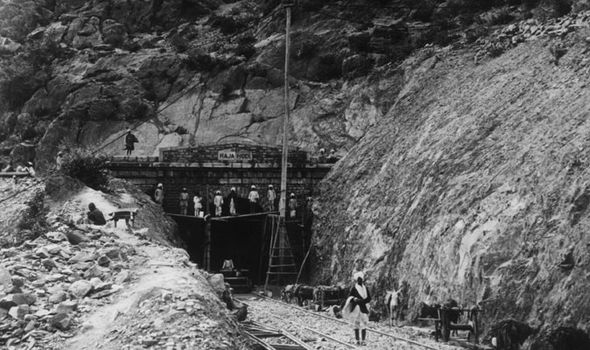

[Reported conversation] The Land Acquisition Act came into being in 1894, in a specific context. The Crown took over from the East India Company in the 1860s, immediately after the revolt of 1857. During these thirty years, the growth of private capital in India was encouraged, as it was already, for instance, from 1853 onwards with the railway construction, essential for opening up the trade routes. The East India Company and other private companies could do it essentially because they had control over the lands through which the railways passed. They had annexed most of those territories. The Land Acquisition Act becomes necessary in the 1890s for the British, as they need to fulfil two purposes: trade, but also the military. The country is vast, and the control must be enhanced, from Pakistan to Burma. The railway developments laid the grounds

for land acquisition practices At this stage, the Land Acquisition Act has two components. First, it satisfies the interest of the Crown. Beyond the East India Company, the Crown is now putting the trading element into the wider context of what British capital requires, all over the Empire. Second, the eminent domain is vested in the Crown, which is now owner of all lands. In this process, the Crown already prepares to offer compensations to those whose lands have been taken. After Independence, the Land Acquisition Act changes, through specific amendments. Control gets transferred from the divinely ordained ruler, the Crown, to the democratically elected apparatus, the Indian State. Now, the State is not just responsible to capital, and to protect it against resistance movements, but also, at least theoretically, to the people. In a sense, it had to cater to the demands that emerged during the Independence movement. For the peasantry, this took the form of two major demands. First was the distribution of land. The marginal peasant, the landless and the poor peasant had to get entitlements to land. This would be reflected in the Tenancy and Land Reforms Acts of the early 1950s. Second was the demand for credit at cheap rates. The British were promoting credit at very steep rates, and the Bengal Famine was a classic example of how usury and extortion by trade and money lending could impoverish huge chunks of the peasantry. Now, credit had to be available. This led to the Co-operative Credit Societies Act, in 1954.

As the land reforms, the credit co-operatives and the amendments to the Land Acquisition Act come together, the logic becomes clear: it is the responsibility of the Indian State to acquire land in the name of the people, but this must be for public purpose. In the welfare state of the 1950s, this public purpose was fairly clear. In the early years of the Land Reforms Act, and with the Land Acquisition Act, till the 1960s, a certain amount of land was acquired for redistribution. But by the 1960s end, the rich peasantry and the landlords start to reorganise and take the bureaucracy along with them. The good done under the land reforms starts getting stopped, diluted. By the early 1970s, the landed gentry made these various acts and reforms redundant from the point of view of public purpose. The first non-Congress governments, from the 1970s onwards, change the character of electoral representation further, and the idea of a welfare state acting on behalf of the poor gets even more diluted. Via the 1980s, this dilution leads to the 1990s, where it is now very visible that the entire welfare state policy has been reversed, replaced by growth policy: the assumption that growth would take place where capital flows, and that the benefits would trickle down to all parts of society. This happened as the country opened to the liberal market, under the pressure of threatening world institutions. This background is necessary to understand how the current government has completely surrendered the welfare road, and openly declared that its main task is to open up to the market, not just for private capital, but essentially global capital. The Gujarat experience probably led the BJP to believe that they could continue acting so blatantly. It was translated in their favour in the elections following the Gujarat riots. But the Delhi Elections of this year seem to mark a watershed, and made them pause. As the new Land Acquisition Bill is discussed, even farmers’ organisations and workers’ organisations affiliated with the BJP are protesting! This is a class analysis of the whole process: the different classes that compose society are getting polarised, even though they may be under the same political umbrella. The BJP may now factor that in their calculations. Polarisation of classes…

and starking contrasts What possible paths are lying ahead? Three sets of responses seem possible:

One should perhaps go a step further and ask that not only the State must be reclaimed, but the instrumentality of the State too. This is arguing that the Land Acquisition Act cannot be used to acquire land from the poor, for the rich. If at all it has to be used, it should be for distributing land to the poor.

The actual reorganisation of political forces will determine how the country evolves on those broad questions. If this current phase leads into either of the first two aforementioned paths – even compensations or doing away with the Land Acquisition Act – our system is likely to crumble and die, with the second one making it last a little longer. In fact, doing away with the Act opens land acquisition further to the market. The BJP could now say, “Leave it to the private sector to negotiate privately with the farmers, and take over the land…” Only returning part of the land to the State would be required. The rest can be developed. This is a logic that the BJP would be perfectly eager to accommodate. Either of these two processes have ultimately very little meaning in terms of political realignments. The situation could be different if the third possibility emerges from the present debates. This would be stating: we want the Land Acquisition Act, but this Act should be tied to the eminent domain of the people, and not of the State, because this is a Republic. Unlike the divinely ordained Crown, here the power lies with the people. Along with this rather straightforward argument, the second necessity is to redefine public purpose. Land acquisition can only be used for public purpose, but this ‘public purpose’ is not what the executive determines it to be – which is the line that the courts have taken. Hypothetically, my prescription would be to tie this public purpose with the Directive Principles. The Directive Principles embody public interest. The public purpose has to be considered only within the context of the Directive Principles, and even the public cannot demand public projects that would lie outside the frame of these Principles. Going to Constitutional legitimacy may indeed be the necessary resort. This text is a reported conversation

with Satchin Joseph Koshy & Samuel Buchoul for LILA Inter-actions |

||||||||

|

Divya Trivedi is a journalist with Frontline, New Delhi. She is an Alumnus of Asian College of Journalism, Chennai, and St Xavier’s College, Kolkata. Previously, she wrote with The Hindu and Business Line, in Gujarat and Mumbai. Divya Trivedi writes on questions related to caste, gender and social justice.

|

Dunu Roy is Director and Founder of the Hazards Centre. For the last three decades, he has been a major activist, agent and initiator around concerns of urbanism, development, technology, engineering and environment. The Hazards Centre is a multidisciplinary team assisting marginalised groups, communities and labour associations as they face difficulties in their fields.

|

||||||||

Debate

Land Acquisition for the PeopleC.R. Yadu |

_Continued |

|||

|

||||

|

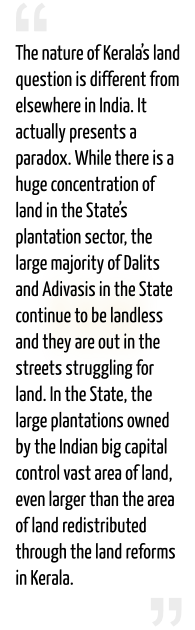

The talk of land acquisition is usually around ‘eminent domain’ or the forcible power of the government to take away private property, mostly for giving it to corporates. What if land acquisition was thought of in the reverse order of this logic? What if the present debate itself can constitute land reforms? The state of Kerala presents such a case where the government should take away the lands from the private corporates and redistribute it to the people.

The rationale for this kind of a new land acquisition needs to be seen in the specificity of the land question in Kerala. The nature of Kerala’s land question is different from elsewhere in India. It actually presents a paradox. While there is a huge concentration of land in the State’s plantation sector, the large majority of Dalits and Adivasis in the State continue to be landless and they are out in the streets struggling for land. In the State, the large plantations owned by the Indian big capital control vast area of land, even larger than the area of land redistributed through the land reforms in Kerala. The vast tea plantations

of Harrison Malayalam Ltd. The root cause of land concentration in the plantation sector can be traced back to the land reform of 1970. The land reform excluded plantation sector from its ceiling provisions. To put it rightly, the plantation lobby in the state could pressurise in such a way that the legislation affected them the least. But land concentration is only part of the story. A large part of the land owned by these big plantations are unutilised, violating the provisions of the Kerala Land Reforms Act 1969. It has been estimated that out of the total cultivable land available in the state, 5.5 per cent is held by two big plantation companies, namely Kannan Devan Hills Produce Company Ltd and Harrison Malayalam Ltd. The Harrison Malayalam Plantation Company of the R.P. Goenka group alone holds in lease almost 25,000 hectares. This shows nothing but the importance of large plantations in Kerala for the land question of the State, especially when viewed from the context of distribution and social equity. Land concentration is not the only phenomenon that complicates Kerala’s land question. The continuing role of plantations in land-grabbing, in different parts of the State, adds insult to injury. It has been found that the two largest plantations in the State … ↗ |

… illegally occupy vast tracts of Government land. According to some media reports, the Harrison Malayalam company has 76,769.80 acres of land in eight districts of the state. It is also said that after 1970, this company has alienated 12,658.16 acres of land in violation of the Kerala Land Reforms Act. The lease period of many of its estates, involving more than 6,000 acres has long been over. The case of Tata’s is no different. In an affidavit filed before the Kerala High Court (W.P. (C) No.8312/2014), the Government stated that the extent of 58741.82 acres of land, mainly in the Kannan Devan Hills Village in Devikulam Taluk, is based on fraudulent documents. Also, in a report submitted to the Kerala High court, the district administration alleged that the Tata group owned Kannan Devan Plantation Company is the largest encroacher of Government land in Munnar. The company is also found to have violated the lease conditions. Recently, media reports claimed that the Tatas have encroached upon more than 1000 acres of forest land in Munnar. It is also reported that in Virippara, the company has transformed 625 acres of forest land into tea plantations. Resistances to the Adivasi exclusions…

also on land matters On yet another side of Kerala’s land question, Dalits and Adivasis are suffering from ‘triple exclusions’. First is their historical exclusion. Dalits were denied land ownership in the feudal agrarian set up of the region. Second is their exclusion from the land reforms. Dalits had to be satisfied with the tiny pieces of homestead lands, which were inadequate to even put up a house. Thirdly is the ongoing process of their exclusion from the land market. The real estate boom and high land prices in the state is exclusionary for the marginalised. It has become highly difficult for them to own land through market mechanism. The land concentration in the plantations and the land deprivation of the marginalised are two sides of the same coin – both showing up from the deficiencies of the land reform. Therefore, there is a strong case for a second-generation land reforms in the state – land reforms that will take away all encroached, unutilised and unauthorised lands of the big plantations and redistribute it to the landless and marginalised sections. This will go a long way in resolving the land question in Kerala. C.R. Yadu is a researcher based in Kerala. He is currently a doctoral scholar at Centre for Development Studies (CDS), Trivandrum. His main areas of interest are agrarian studies and the informal labour.

|

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images and videos courtesy: DM Studio | Wikipedia | Kafila | Kafila | Express | Scoop Nest | Metro Vaartha | The Hindu Business Line

Voice courtesy: Shriyam Gupta

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||