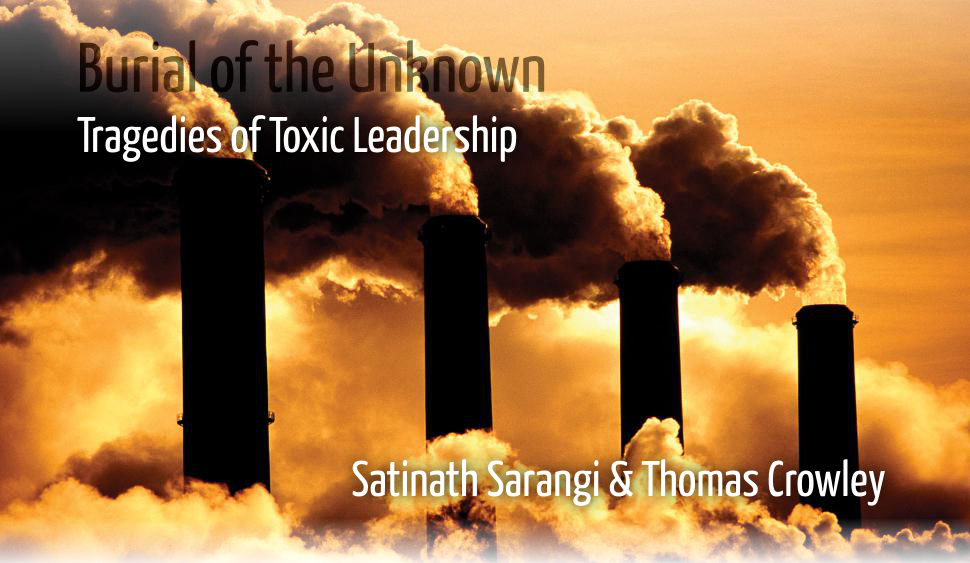

12 December 2014The cloudy skies and dried soils have conveniently become characters in a too comfortable tale: they are, we are told, the necessary casualty of history, as humans spread over the world, building societies and connecting nations. Like the friendly ‘Dhruzba-Dhosti’ vision of Modi and Putin, a few days back, celebrated as an early move of collaboration within the ‘new world order’. This was only to forget that this sudden amity was an essentially interested one, looking forward to signing the deal of 12 supplementary nuclear plants in India before 2035. One could, or perhaps, should feel a sense of discomfort, as these international industrialist efforts have come to disturb the thirtieth anniversary of Bhopal’s mourning. But, on the antipodes, Southern American voices were just raising at the public rostrum of the yearly UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The voice of an alternative, not only in dreams but in recorded reality, as a few valiant leaders reaffirmed the positive results of another understanding of land, placing the necessary use of the earth’s bounty in the hands of the very inhabitants of each area. Only this binding, this renewed stitch between each community and its earth knowledge, can strengthen the continuity of locals towards the translocal, reaching finally, one day perhaps, the scale of the global. This week on LILA Inter-actions, Satinath Sarangi recalls the diplomatic, economic and legal ties that pushed the risk of the UCIL plant of Bhopal into a reality, and he comments on an environmental economy that has visibly not learnt from such a traumatic lesson. Thomas Crowley analyses the subversive resistance of Evo Morales, and the remaining hurdles on the ground, to suggest a deep rapport between environmental and political economy with the help of eco-philosophy and Marx. Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations. |

|||||||||

The Casualties of Environmental RacismSatinath Sarangi |

Grand Theft CO2Thomas Crowley |

||||||||

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

Listen |

Listen |

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

||||||

|

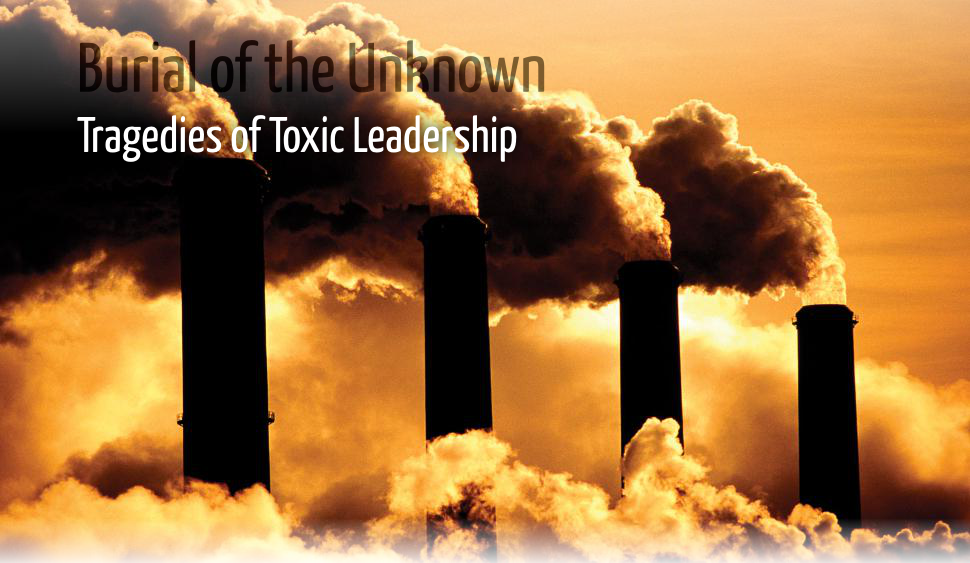

The Bhopal disaster did not start on 4 December 1984. The immediate context of the Union Carbide disaster in Bhopal is the Green Revolution, which was but a grand business plan hatched by chemical corporations peaking during second world war to continue with business in peace time, by waging war against insects and soon after against weeds, fungus and most everything else with synthetic poisons. Union Carbide was close to the Pentagon from the First World War, and its Oakridge, Tennessee plant processed large parts of the material for the bombs dropped on Japan during the Second World War. The support Union Carbide received from the US government was manifest in several ways. Wikileaks documents show that Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State personally made sure that the US government facilitated the EXIM bank loan (curiously, for an Indian company) to set up the Methyl Isocyanate plant in Bhopal, that would later become the site of the world’s worst industrial disaster. Because Union Carbide was close to the US government, it was accorded special favours by the Indian government. Allowing Union Carbide to hold majority stakes, as an exception to the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act that forbade majority holding of an Indian subsidiary, was one such special favour. Within the overall ‘systemic’ support that Union Carbide received from the Indian government, there were individuals who had their own reasons to be favourable towards the American multinational. Thus, Arjun Singh, Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh at the time of the disaster, was known to have received, as a patron of the Churhat Children’s Relief Trust, large sums of money from Union Carbide and the corporation’s plush guest house was used as a clubhouse for politicians of the ruling party in the state.

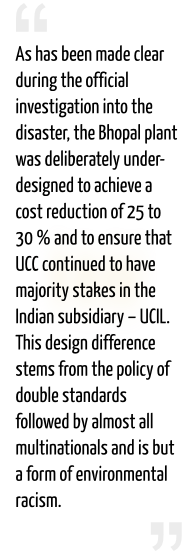

While the immediate cause of the leak was the malfunctioning and absence of safety systems, the real causes of the disaster lay in the design differences in the MIC plants in Institute, West Virginia and in Bhopal. As has been made clear during the official investigation into the disaster, the Bhopal plant was deliberately under-designed to achieve a cost reduction of 25 to 30 % and to ensure that UCC continued to have majority stakes in the Indian subsidiary – UCIL. This design difference stems from the policy of double standards followed by almost all multinationals and is but a form of environmental racism. This policy is apparent once again in Dow Chemical accepting and honouring liabilities of Union Carbide in the US, but refusing to accept Union Carbide’s Bhopal related liabilities. At a national and local level, the official response to Bhopal, immediately after the disaster and in the following decades, has been the protection of the interest of the corporations, and the neglect of the survivors’ needs. The first official act was not to warn people to run against the wind or put wet cloth over nose and mouth; it was to organise vehicles and men to pick dead bodies from the streets and dump them into the Narmada River, and forests outside the city. For all practical purposes, the policy followed by successive Indian governments, irrespective of the political party in power, has been one where justice in Bhopal was seen to be leading to jeopardising the investment climate. Warren Anderson could avoid trial in India

In this context, the litigation by the Indian government (on behalf of the Bhopal survivors as per the Bhopal Act, 1985) against Union Carbide can best be seen as a mock battle. The settlement of 1989 was the most blatant manifestation of the collusion between the Indian government and Union Carbide. The feet dragging by the prosecution, Central Bureau of Investigation on the matter of extradition of Warren Anderson, by the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilisers in intervening in the ongoing suit on toxic contamination in the US Federal court, and the absence of any criminal action against the absconding corporation, are few of the many instances where the complicity of the Indian government is manifest.

The catastrophe in Bhopal was a result of deliberate decision-making, aimed at profit maximising and control gaining of a subsidiary, by senior corporate officials who were fully aware of the consequences of the risks they were imposing on the local population. Such corporate crimes are at the root of environmental tensions in large parts of the country and most intensely in the industrial estates where slow and silent chemical disasters of magnitudes comparable to Bhopal are ongoing. Going by the daily experiences of the communities in the vicinity of industrial estates such as Vapi and Ankleshwar in Gujarat, Taloja and Lote Prasuram in Maharashtra, or Cuddalore and Mettur in Chennai, the chemical and other hazardous plants operate in these areas in an atmosphere of near absent surveillance and regulation, and lawbreaking by the rich and powerful plant owners are routine. In fact, Bhopal also illustrates the power asymmetry of such environmental and social disasters. While the offending corporation, Dow Chemical, is the second largest chemical corporation in the world, the victims of the crimes of this corporation (as well as that of its 100% subsidiary Union Carbide) are 48 % Muslims and majority of the 49 % Hindus are from low castes. 70 % of the survivors are known to be earning their livelihoods through hard physical work. The Bhopal anniversary coincides with the yearly environmental conference of the UN, this year in Lima, Peru. But the failure of the United Nations to respond to the ongoing disasters in Bhopal is significant in the context of the response of this international agency to disasters that are seen as ‘acts of god’. The repeated pleas by survivors’ organisations for help through expertise and other resources by the WHO in matters of health care, by UNICEF towards children, by the ILO for workers disabled by the disaster and by UNEP in the matter of contamination of soil and groundwater in and around the abandoned Union Carbide factory, have yielded little else but hollow assurances. The UN has failed to act in any manner so as to stop the two American corporations from violating the human rights of the Bhopal survivors, and it has taken no steps towards creating a supra-national forum for adjudicating on violations by multinational corporations. |

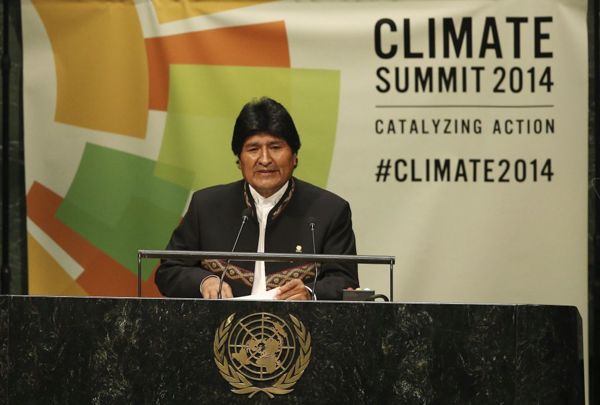

Thank god for Bolivia. Or rather, thank Gaia, or Madre Tierra. Amidst all the platitudes and diplomatic superficialities of the 2014 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 20), Bolivian president Evo Morales has fulfilled the role of moral gadfly yet again, delivering blunt truths to the assembled crowd. Among his exhortations: “Our indigenous forefathers taught us that a just society must be based on three principles – not being a thief, not being a liar, and not being lazy.” The implication, of course, is that the developed world has violated all three of these principles, something Morales spelt out more explicitly later in the speech: “There are some greedy countries that want to consume all of this atmosphere on their own. These countries have stolen from us in the colonial period, and they are still stealing from us – they are stealing our future, and the possibilities to develop ourselves in a sustainable fashion.” Evo Morales at UNCCC 2014

His speech was delivered on behalf of G77 + China, a motley group that includes much of the global South, and is meant as a counterbalance to the power of the United States and Europe in the United Nations. But the speech had a Bolivian – and more broadly Latin American – flair, appropriate given the Conference’s location in Peru. Morales asserted that Latin America is one of the regions hardest hit by climate change, and that the region is leading the way in the push to protect the earth based on an appreciation for life, rather than the compulsions of the market. Environmental philosophers have paid close attention to this kind of rhetoric, especially as it comes from a world leader (albeit a renegade one). I found out about this speech, in fact, from the email listserve of the International Society for Environmental Ethics. There was also much rejoicing in eco-philosophical circles after the passage of Bolivia’s 2010 “Law of the Rights of Mother Earth,” which, among other things, gives ecosystems legal standing. The language of this law shares much with the rhetoric of radical eco-philosophy, which puts a strong emphasis on the intrinsic value of nature, apart from its usefulness to humans.

A recent analysis of the Bolivian law, though, shows the difficulty of implementing the ‘indigenous wisdom’ promoted by Morales while the global economic system is pushing in another direction. Despite important steps – both rhetorical and practical – to distance itself from neoliberal practices, Bolivia is still very much enmeshed in the global economy. It earns about 500 million USD a year from mining companies. This makes up a full one-third of Bolivia’s store of foreign currency, which is of vital importance for the country’s economic health. (Depleted supplies of foreign currency have been at the root of numerous economic crises in India, most significantly the ‘balance of payments’ crisis in 1991, which led to India’s wholesale adoption of neoliberal economic policies.) These realities suggest that there are daunting challenges facing those who want to create a world that actually values nature and accords it real rights, legal as well as ethical. It is all well and good to state that ecosystems, or other species, have intrinsic value, but the dominant socioeconomic system in the world today acts as if this value does not exist. The effects of this system are all around us, with global warming as only the most prominent example. These socioeconomic realities also help explain why, indeed, there has been no justice in the Bhopal case. Philosophers concerned with environmental issues must deal with the nitty-gritty of political economy if they want to apply their philosophies to ongoing ecological struggles. To put it in philosophical term, there is a need for phronesis (Aristotle’s term for practical wisdom) in the application of environmental ethics. There is ample precedent for this in the history of philosophy. Back when disciplines were not so neatly defined, philosophers easily moved from the natural sciences to economics to ethics and metaphysics and on and on. The founders of classical political economy, including Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill, were philosophers who had written extensively on moral matters. Karl Marx

Karl Marx, too, had a philosophical pedigree; he wrote his doctoral dissertation on the materialism of Epictetus. Marxism, and communism more generally, has picked up a reputation as being anti-ecological, but Marx’s writings are a rich source of ecological thinking (as John Bellamy Foster has argued at length). Capitalism, in Marx’s view, creates an ever-widening “metabolic rift” between humans and the rest of nature. An economic system that requires endless compound growth cannot coexist with a planet that has limited natural resources.

In the present day, as the COP 20 limps on and as the Bhopal disaster marks its 30th anniversary, Marx’s framework could serve as an inspiration for eco-philosophers to ground their ethical theories in a thoroughgoing analysis of political economy. Of course, he would have to be updated for the twenty-first century. In Marx’s time, the main ecological disaster was the depletion of soils worldwide. As Marx says in Capital, All progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the workers, but of robbing the soil; all progress in increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time is a progress towards ruining the more long-lasting sources of that fertility… Capitalist production, therefore, only develops… by simultaneously undermining the original sources of all wealth – the soil and the worker. Given the realities of global warming and recurrence of airborne toxic events, including Bhopal, it is time to add the atmosphere to the list of resources being squandered away. Evo Morales clearly understands this; it remains to be seen whether the rest of the world will respond to his clarion call. |

||||||||

|

Satinath Sarangi is the Founder and the Managing Trustee of the Sambhavna Trust Clinic, in Bhopal. The Sambhavna Trust Clinic, also known as Bhopal People’s Health and Documentation Clinic, opened in 1996 to provide communities affected by the aftermaths of the 1984 disaster, with therapeutic solutions, free of cost. Satinath Sarangi has been a major campaigner for the cause of the Bhopal disaster for the last three decades, writing extensively and fighting national and international legal cases. He and the Trust have received several awards.

|

Thomas Crowley is a Delhi-based writer and editor. He studied ecological philosophy as an undergraduate at Yale University, writing his thesis on the use of evaluative terms in environmental discourse. As a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Pune, he researched the intersection of Indian philosophical, religious, ecological and political trends. He is currently working on a project about the political ecology of the Delhi Ridge.

|

||||||||

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images and videos courtesy: My Blog 0411 | BBC | COP 20 | Etsy

Voice courtesy: Shriyam Gupta

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||