2 June 2014Our age has become a literal Nanjing Road: wordy devices of love, billboards and news hours clamour for our sensory apprehension and instant approval. Not so long ago, we knew the word as medium, signifier, a means to a meaningful end. Today, our words seem to allow themselves to be readily flung into violent stage shows of information, analyses, comments and opinions. Amidst these carnivals of tautology, could we reclaim the word as an inspiring playground of the beautiful? If we reassess traditions of beauty in language, we may receive the topically relevant realisations of Japanese aesthetics, for instance, organised around the principle of MA, the silence that separates words and thus gives them enough space for their meanings to emerge. Or Ghazal poetry, perhaps, which sets at its heart the creative tension between contrary terms, an aspect that our noise-afflicted media world could lease for life. In this week’s Inter-actions, Haiku poet Kala Ramesh celebrates the quest for the succinct in her favoured tradition. Poet-Physicist Len Anderson discovers Ghazal and physics as the two sides of his search of the unknown. |

Hold the cursor on the illustrations to display animations and descriptions.

A Medium of BrevityKala Ramesh |

The Physics of PoetryLen Anderson |

||||||||

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

Listen |

Listen |

Requested file could not be found (error code 404). Verify the file URL specified in the shortcode. |

||||||

|

Shabda. Mauna. Shunyata — these three words form the basis of a search that I have explored for many years now, trying to understand something that all scriptures say is within us. Tao says: Thirty spokes share the wheel’s hub; From childhood, I have been a student of both Carnatic and Hindustani classical music. Later, I began to pursue classical vocal under the guidance of Vidushi Shubaddha Chirmulay and spent hours, no, years, trying to master Pandit Kumar Gandhava’s gayaki, his compositions and the nirguni bhajans of Sant Kabir and Sant Gorakhnath. I made a concerted effort to understand the ‘spirit’ behind Kumarji’s gayaki – incorporating the vigour and the vitality so inherent in his style of singing. It was a journey that dug deep into the resources of my creative ability and demanded great persevering skills for more than fifteen years. Being familiar with the Indian practices of art forms such as dance, drama and painting, I strongly believe every genre feeds into another, enriching the root source of one’s creativity. In 2005, accidently, I got introduced to haiku. There began my passionate search for images that colour one’s mind and imagination. The evolution of haiku from Zen Buddhism, and their interrelation, is a historical controversy. Without entering this debate, I firmly hold that creativity in any form is to a great extent spiritual. The Buddhist monk Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) The phrase “form is emptiness; emptiness is form”, perhaps the most celebrated paradox associated with Buddhist philosophy, is exemplified in various art practices in India. For a Hindustani classical vocalist, the truth of this statement becomes evident as her voice fades into the void… and her continuing phrase in the raga expansion arises from the void again. It is also significant that Indian music is not notated; it is sung and played extempore, to ensure this movement. deep in raga –

Haiku is an exacting art form. For the most part, it is elusive and difficult to understand but it still looks deceptively simple. At first glance, the language and the size hoodwink the intensity of the emotion it holds or the level at which it can move the reader. Haiku is made up of unadorned words requiring no special knowledge of a language to be enjoyed. A haiku’s strength lies in a world of concrete imagery, and surely not in merely understanding the words as they stand. There is a famous saying that goes: ‘If you point to the moon with a bejewelled hand, all I see is your hand.’ So it is in creating a wordless poem, almost – if that is possible – that the bare beauty of a haiku comes forth. Haiku is often called a ‘wordless poem’, since the words, so simple, seem to drop away, leaving the stark image, alone, in your mind! The principle of ‘the less, the more’ is implicitly followed in contemporary haiku all over the world. mountain bridge Can one call haiku a word painting, something frozen in time? In film jargon, we could refer to each haiku as a ‘shot’, for it captures more than a frozen moment. This poem, in just about seven to ten words, shows the passing of time, the transient, the fleeting and thus, brings into focus the creative forces working in nature. Therein lies the difficulty. the sea darkens–– — Matsuo Basho Look at the synaesthesia here. Can a duck’s call be white? This makes us sit up, and take notice. It makes the poem memorable. The last image links to line 1, which talks about the ‘darkening sea’, so all that I get, as a reader, is a white bird, perhaps a migrating bird flying and getting smaller and smaller. The shape disappears, leaving only the colour, and its honk, thus it becomes, for me, ‘white’… The truth of the moment seen in an extraordinary way! Each word has an important and crucial place in the poem, since in haiku, there is no room for redundancy.

Haiku employs what is known as the cut — the kire in Japanese language. This is a subtle way in which the juxtaposition of two images acts in a fashion similar to a spark plug in a two wheeler – they help to connect… and this spark of understanding or recognition is what haiku is all about! To this, I add the core ingredient of haiku: the art of suggestion. The famous Bharatanatyam dancer Rukmini Devi Arundale said that Abhinaya, or the rendering of the various emotions through body and facial expression in dance, needs to be mere suggestion, anything more becomes drama. A tall order! We all know that in the silences between notes, between words, between lines, the emotions that arise are rasa — the aesthetic essence — which gives poetry, music or dance, a much greater sense of depth and resonance. Rasa is something that cannot be described by words because it has taken us to a sublime plane where sounds have dropped off. The most important aspect of rasa, the emotional quotient, is that it lingers on, long after the stimulus has been removed. We often ruminate for days over a haiku or a song we have read or heard, savouring the joy of its memory. What Rasa does to Indian aesthetics is exactly what the Japanese concept of MA does to Renku – a collaborative linked verse tradition. It is found in haiku between the verses and the juxtaposition of two images. MA is the name given to the intentional pauses scattered over our language utterances. It is MA that allows for words and meanings to stand out. In music, it permits the resonance of notes. An echo of the Buddhist notion of Shunyata (emptiness), MA is essential to Japanese aesthetics, referring to the ‘empty net’ on which things can be, stand out and mean. I believe that efforts should be made to discuss Rasa and MA together, and to see how the Japanese notion connects with the famous concept of Indian aesthetics. The silences and pauses in haiku and in raga music, and what this does in the rasika’s mind, fascinate me. Some examples of my haiku: morning raga… muggy weather temple bells liquid sky . . . – Kala Ramesh, Notes from the Gean #4, 2010 “Some haiku come to me slowly. It takes awhile for them to grow and develop with meaning for me. Others are like this. Instantly I loved it. To begin with, “liquid sky” seemed a fresh and exciting way to name a rainy day. Okay. Then comes the image of “a steel bucket hits” and the monkey mind is saying, “Shouldn’t it be the rain that hits the bucket and not the bucket hitting back?” A riddle is formed and in the third line, as is proper, the answer that solves the puzzle is given – “well water”. Ah, the liquid sky is not a rainy cloud in the sky but the sky deep in a well. Yes, that is sky too when the water reflects what is above it. Now, it makes sense for the steel bucket to hit the sky, when it drops in the well. The penny drops and I have solved the riddle of this haiku. As a reader, I feel smarter, refreshed, renewed with this word coinage: ‘liquid sky’.” I conclude the reflection on this observation: beauty is inherent in all art forms, and in poetry, when we lift it above words, it becomes almost spiritual. My firm belief is that this blend of beauty with spirituality is what makes haiku sublime and memorable.Unless otherwise mentioned, |

I am a physicist and poet, poet and physicist. In both physics and poetry, and between them, I have explored beauty. This navigation between the two was both a quest and a discovery, and helped me reach a new understanding of the nature of beauty, as well as find ways of creating it. In research teams and collaborations, I have done experimental research in nuclear and elementary particle physics, measuring the momentum distributions of protons inside light nuclei, and of quarks inside protons and neutrons. In other words, deep inside us, inside the nuclei of our atoms, there are very, very tiny things held together by attractive forces and wiggling. The stronger the attractive force that confines them, the smaller the nucleus and the faster those tiny things inside it wiggle. Constraint implies movement. The power and beauty of this understanding and the mathematics that describes it remain amazing and beautiful to me. Then, I went into the industry. I developed sensors for measuring moisture content, coating thickness and the strength of paper as it whizzes by at thousands of feet per minute on a paper machine. These qualities determine whether the paper can be sold or must be ground up into fibres again… which would mean that the paper machine and all the people running it would have to try all over again to make what the customer will ultimately buy. The trajectory and fruits of my quest were extending into the outside, into the industry, and into the market. But one morning, on my way to a field trip, I twisted my back, rotating three vertebrae and pinching my sciatic nerve. The chronic pain in the backs of both legs made it impossible to do deskwork all day. Soon, I resigned from my job. I decided I would retire early to turn my life toward an old part of me: poetry. And this time, I eventually came to dedicate myself fully to it.

I had been writing poetry off and on ever since high school, when my English teacher asked each of us to write a poem. It was 1960, during the Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union. Mine was about the aftermath of a nuclear war and began with the first line, “Alone I walk with twenty million others.” When my best friend read it, his reaction was stark: “Are you sick or something?” Decades later, I would say that it was civilisation that was sick, and that I had only inherited some measure of its illness. In fact, I was struggling to describe the illness, in search of healing. What I kept from this moment, irrespective of the quality of the poem, was that I had struck a chord, and I was impelled to continue. I studied some of the poetic forms inherited from European tradition, but none of them appealed to me, so I wrote in free verse. However, thanks to Robert Bly, a man who endlessly encouraged the translation of poetry into English, one day the Ghazal came into my life. Robert Bly I fell in love with this form. The freedom in creating the disjoint couplets was a real delight for me. I relished their epigrammatic character, the challenge of saying something in two lines and being able to shift and say something rather different in the next two. I valued that jumping between stanzas and the process of cooking something meaningful down to two lines. I could make a richness that would never occur to me otherwise. Thus, I experienced for the first time a form providing a challenge that opened my mind instead of getting in my way. Constraint brought a kind of freedom. In ancient Greece, it was said that poetry was an art form that had no rules. One could take all the powers that language holds and apply them as one dares. We have returned to this view. Of course, we would be wise to observe the consequences of our inventions and learn from them to realise their powers and manage their weaknesses. We should remember that every form was originally created by breaking another, even if we no longer know what that original form was. Like other rules, forms are made for breaking. We are free, free in our chains. Another thing that I learned, in particular through Ghazal, was that I liked bringing together contrary energies. The tension between them brought more energy into the poem. The disjoint character of the couplets opened this up for me, but I could also do it within a couplet or even within a single line. These energies stir me as a reader and keep me engaged with a poem. Eventually, I read William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “Without contraries there is no progression.” This awareness slowly grew in me.

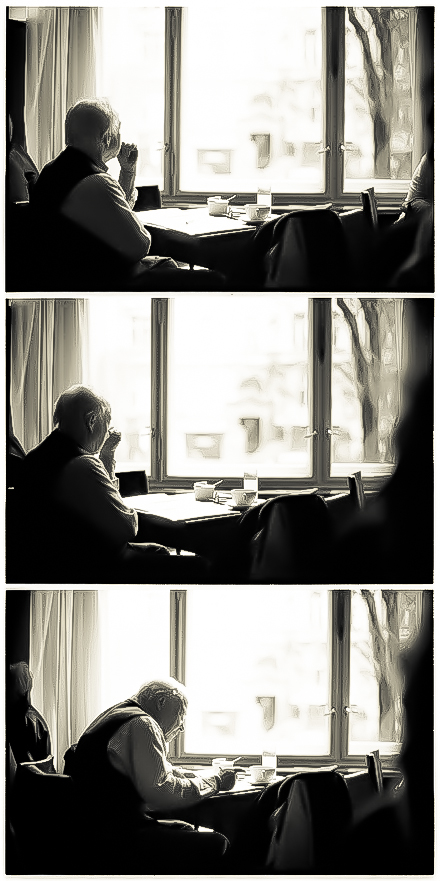

It helped me understand better how I could be at once a poet and a physicist, and not only get away with it, but benefit by bringing these disparate sides of my character together on the page. These are contraries. And contraries are needed for movement. If you want to leap, you must be bound to the earth by gravity, so that your muscles can push against the immovable earth to propel you upwards into the air. I have learned to love contraries. I even created a poetic form that requires a pair of contraries in each couplet, with no rhyme or refrain required. I could re-discover the richness of my own contraries. From adolescence I loved to tinker with equipment. However, science also allowed me to express my intense intellectual curiosity. I had a lot of questions and science helped me learn to ask them. It also taught me the value of doubt. A theory that has not been tested is just a theory. And a theory that allows no means of testing, as Karl Popper taught us, is a theory in its early stages. Theories are broken by new theories and broken by experiments that show their falsehood or limitations. As a poet, I also love to ask questions, to explore them and to respond to them, in language, with my own personal experience. And then tinker with that language, often opening up other responses to weave around the questions. Thus, poetry, like any form of art, is a discovery process too. And that process is what drives me, what I value most. So, in a sense, one thing has driven me in science and in poetry: the unknown – its immensity, our uncertainty in wanting to know it, and in facing it. Usually, when I write, I sit down and read from a book by one of my favourite poets for a while. Often, as I slip into the poetic way of being through the poems, I feel a deep vulnerability, which I can only express as the sense that language cannot contain or voice what we long to know or to speak to others. I feel despair, and tears well up, even if I am sitting in a café with people all around me. Then, I close the book and pick up my journal and pen. I don’t know what I am doing. I say to myself that I surrender and will write anything I am offered. I feel fully surrendered. This is how I make the first draft of a free verse poem. My muse or my unconscious gives me something, and I am grateful. Later, I do the work of fashioning a real poem from it. I could never have imagined or sought such a bizarre process! It was given to me. And each time, it is given to me again, without my asking. In this giving and receiving, poetry writing, and Ghazal in particular, becomes for me something quite different from science. My vision of the unknown, I believe, is confirmed by our continuing discoveries in astronomy, cosmology and elementary particle physics, but also cognitive science. But I see no reason to believe that our quest will be realised. It does not have an ending, a destination. Science and poetry, like civilisation, are rightly understood as processes that will go on. We will always be merely human in the presence of a greater unknown.

|

||||||||

|

Kala Ramesh is an exponent of Hindustani classical vocal music and she has written more than 1000 poems (comprising haiku, senryu, tanka, kyoka, haibun and renku), published in various reputed journals and anthologies from around the world. Her work can be read in two publications: Haiku 21: An Anthology of Contemporary English-language Haiku (Modern Haiku Press, 2012) and Haiku in English – the First Hundred Years (W.W. Norton 2013). Kala enjoys teaching haiku and other allied genres to school children and to undergraduates of the Symbiosis International University, Pune. She is the editor of modern haiku at Under The Basho, and the Chief editor of Youth Corner at Cattails.

|

Len Anderson is the author of Invented by the Night (2011), Affection for the Unknowable (2003), both from Hummingbird Press, and a chapbook, BEEP: A Version of the History of the Personal Computer Rendered in Free Verse in the Manner of Howl by Allen Ginsberg. He received a nomination for a Pushcart Prize from DMQ Review, is a winner of the Dragonfly Press Poetry Competition and the Mary Lönnberg Smith Poetry Award, and received the 2011 Dragonfly Press Award for Outstanding Literary Achievement. He is a co-founder of Poetry Santa Cruz. He used to be a researcher in particle physics, and an engineer.

|

||||||||

Disclaimers: The opinions expressed by the writers are their own. They do not represent their institutions’ view.

LILA Inter-actions will not be responsible for the views presented.

The images and the videos used are only intended to provide multiple perspectives on the fields under discussion.

Images courtesy: Columbia | Language-Arts | Rankin Writing | On Prose and Verse | VicciLux | Continuum | Kit Blog

Voices courtesy: Anonymous Female Voice & Samuel Buchoul

Share this debate… |

… follow LILA… |

||||